Photo by Binkiexxx.

Photo by Binkiexxx. Open software is based in a cooperative mode of production, based on personal reputation rather than on economic incentives. Furthermore, open source developers may have a “psychological contract” with their peers, linking them to each other’s work on grounds of trust and values of common interest (Chong, Sae & Shui). However, the sustainable existence of this cooperative form of creating software is enforced by an additional factor, licensing. Open source licenses can be seen as a mechanism that helps to give a structure to the relation among developers working on open source; in this sense, licenses become a “mechanism for social ordering” (Berry, 2008).

The major difference between free and proprietary software is their licensing model. The license is a set of regulations or conditions that an author sets for using its work. The license tells the users of any given software how they can use the software and the conditions involved in such use.

There are different types of licenses, and is possible to distinguish marked differences among proprietary and open source licenses.

Proprietary software licenses have a price: it must be purchased in order to be used. When we talk about buying a program what we actually are buying is a license. The source code remains hidden, being known only by the company that creates the software. Making copies of this kind of software is forbidden, and the number of computers where the program may be installed is restricted, we cannot install the software in as many computers we wish. And finally, any modification of the code is not permitted without authorization.

On the contrary, free software licenses are more flexible: they don’t have an economical cost, its code is public and open; the software can be modified by anyone and licenses allow installing it in unlimited number of computers.

However, what sets apart open source licenses is its generative character; taking for example GNU GPL license, we can observe a viral effect. Softwares based on this kind of license must be released with the same license, creating an unending chain of software linked directly with previous developments.

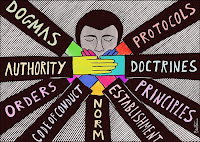

In this creative scheme, licenses applied to open source not only include conditions of use for end users, yet more important, these licenses integrate values and norms for developers reflecting the spirit of this cooperative model.